Sometimes when reading about the Serapeum at Saqqara, or seeing photographs detailing it, the context in which it sits is not seen or realised. So here are some images from Google Earth which show how it is situated.

It seems amazing that such a fascinating site presents itself in such a barren landscape, near to Djoser’s Step Pyramid, yet with such poor signage as to suggest meager interest and a sense of disregarded. Some how, all that is amazing about this construction is not only buried beneath ground, as it was when built, but the wonder and enormity of it also seems dismissed as though that too is to hidden from view. Any significant interest in the Serapeum is not very evident. The old wire fence that surrounds the site is ugly, though not overly visually obstructive, and there is a paucity of information present pertaining to the site in a dilapidated or poor condition. A surprise to see. I would have thought this to be among the most amazing features of ancient Egypt.

The Greek geographer Strabo, who travelled in Egypt around 24 AD, mentioned seeing an avenue of the sphinxes forming a path 1300m long that lead through the dunes towards the Serapeum.

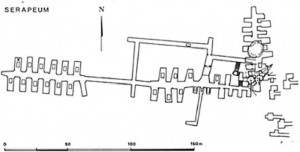

So what is so fascinating about Saqara’s Serapeum? Lots, but probably most especially the twenty four enormous sarcophagi, measuring 4m long, 2.30m wide, 3.30m high and each weighing over 80 tons, made of granite. The Serapeum is an underground development comprising a complex network of narrow tunnels within which the large sarcophagi are located. It is baffling to think how these sarcophagi were ever moved and positioned within such a tightly confined space. Clearly not impossible, as proved, but how?

The sarcophagi too create their own mystery. Only two of them bare any inscriptions. The others are totally smooth in finish. Each is carved from a single block of granite. The corners are perfect inside and out, and the sides are said to be exactly parallel, which, even if there were actually some slight wavering and error in the remark, would remain remarkable with only primitive tools and no drill to have used that anyone knows of. Apparently there are notches that allow the 4.30m wide lid to be rotated sideways on its central axis and to remain in position on the edge of the sarcophagus. This indicates that the sarcophagi were used open as often as closed.

Did these granite lidded boxes ever contain mummified bulls? This has been thought to be their purpose, even though they would have been extra large in comparrison to the size of a bull, and no such remains have been found in them. It does seem weird to think that someone would rob a coffin, and one containing the remains of a bull. The idea for their containing mummified bulls is due to a cult worship which had been in existence for a very long time in Egypt. To the ancient Egyptians, the bull Apis contained the divine manifestation of the god Ptah, and later of Osiris. According to interpretation, when Osiris later absorbed the identity of Ptah, he symbolised life in death, that is to say, resurrection. For a moment this can seem odd and delirious, but then no more so than when compared to any modern held beliefs in a god, gods, divinity, or angels and the like. Mummified bulls have been found in both stone and wooden coffins, but much smaller and matching the actual size for the bull. These date from both the time of Rameses 11 (1303 – 1213 BC, 19th dynasty) and Amenhotep III (1387-1350, 18th dynasty). According to Manetho, an Egyptian priest of the third century BC, this went back as far as the second dynasty. In fact, objects which show the importance of the bull in connection with the heavens have been found as far back as to be from the pre-dynastic period of Naqada (4000-3000 BC).

Did these granite lidded boxes ever contain mummified bulls? This has been thought to be their purpose, even though they would have been extra large in comparrison to the size of a bull, and no such remains have been found in them. It does seem weird to think that someone would rob a coffin, and one containing the remains of a bull. The idea for their containing mummified bulls is due to a cult worship which had been in existence for a very long time in Egypt. To the ancient Egyptians, the bull Apis contained the divine manifestation of the god Ptah, and later of Osiris. According to interpretation, when Osiris later absorbed the identity of Ptah, he symbolised life in death, that is to say, resurrection. For a moment this can seem odd and delirious, but then no more so than when compared to any modern held beliefs in a god, gods, divinity, or angels and the like. Mummified bulls have been found in both stone and wooden coffins, but much smaller and matching the actual size for the bull. These date from both the time of Rameses 11 (1303 – 1213 BC, 19th dynasty) and Amenhotep III (1387-1350, 18th dynasty). According to Manetho, an Egyptian priest of the third century BC, this went back as far as the second dynasty. In fact, objects which show the importance of the bull in connection with the heavens have been found as far back as to be from the pre-dynastic period of Naqada (4000-3000 BC).

As always with such ancient places, the dating of the Serapeum and how its was achieved seems a mystery. The dates which are sometimes stated, such as those for the ‘sarcophagi’, are from around the 18th dynasty, (1540 -1307BC). But even I, a complete layman, of only a curios interest from afar, can read through the information and the photographs available to recognise that such dating is most probably flawed. It is amazing how thought to be scholarly experts expound material as fact and they really shouldn’t. It seems clear that dating needs more consideration. Dates become even more confusing when the lay person reads of an earlier date posited for the sarcophagi as tombs for mummified sacred Apis bulls of the 26th dynasty (664-525 BC), not 18th dynasty. So what is going on with these dates? The dating of the Serapeum, and the bull burials, has been based solely on bits of 18th dynasty pottery found nearby. That hardly seems a guaranteed way to acquire the date for the construction as these could have been placed there at a later date. Given the incredible quality of workmanship of the sarcophagi, this would seem more characteristic of the stone masonry of the early dynasties. Those that possess inscriptions are said to be very poorly drawn, as though written by a clumsy hand and added at a later time than when the sarcophagi were first produced. The hieroglyphs lack the fineness to be commensurate with such quality of masonic work.

Answers to questions that obviously arise about how such a feat of achievement in constructing the Serapeum of Saqqara was achieved have yet to be found. The spaces in which they could have been maneuvered is very tight, their enormous weight would have required many people to have moved them, but where would they have stood to have heaved and positioned them? How were they moved into place? How was such workmanship in making the sarcophagi achieved?

Photo credit: pyramidtextsonline / Foter / CC BY Photo credit: pyramidtextsonline / Foter / CC BY